When I was younger, my dad took me steelhead fishing a few times. He loved it and caught his fair share. I never caught a fish. Instead, I caught countless snags and my enthusiasm for steelheading waned.

We went to the high banks of the Au Sable River, where I could see the fish below. Even when I worked my bait right past their mouths, it just slid by without a single reaction.

He took me fishing on a few trips on the Little Manistee River. I couldn't see the fish, nor all the submerged tree limbs that kept me tying new baits on as fast as I could cast them out.

Needless to say, I went many years without trying to catch a steelhead in a Michigan river. It just didn't seem that fun.

I started fishing with a co-worker, Ron Murray, and he insisted that we go. I was a grown adult now, instead of a 12-year-old. I considered that things might look differently for me if I tried it again. I enjoyed being with Ron, so I agreed to give it another go. Am I glad that I did!

Ron showed me a few things that I probably ignored in my adolescence. He cocked his head, smiled, and shrugged his shoulders when I asked him how confident he was that we'd catch a steelhead. "That's not entirely up to us. The steelhead have the final say." Those are words to live by when it comes to steelhead fishing. Our job is to do the things that Ron showed me, to convince the fish to bite.

Here's what I learned:

Lesson 1: It's a River, Not a Bathtub

The first and most important thing Ron taught me was how to read the water. As a kid, I just saw a moving body of water and cast into the part that looked "fishy." On the Au Sable, I saw those dark shapes holding in a deep, slow pool and assumed that's where I should be fishing.

Ron explained my mistake. "Those fish you saw from the high bank?" he said, pointing with his rod tip. "They're either resting or traveling. They're not actively feeding. You could drag a steak dinner right past their nose and they wouldn't touch it."

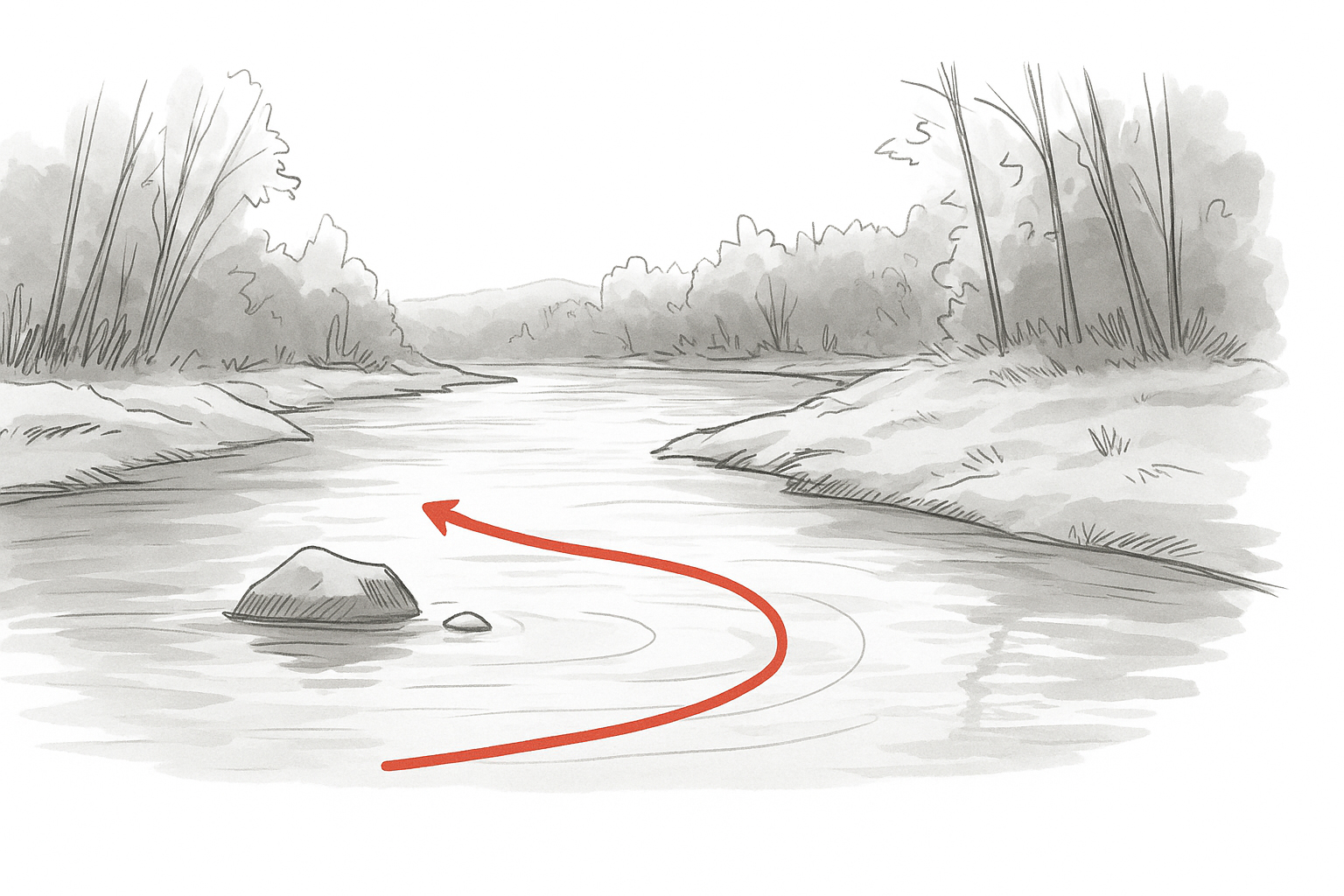

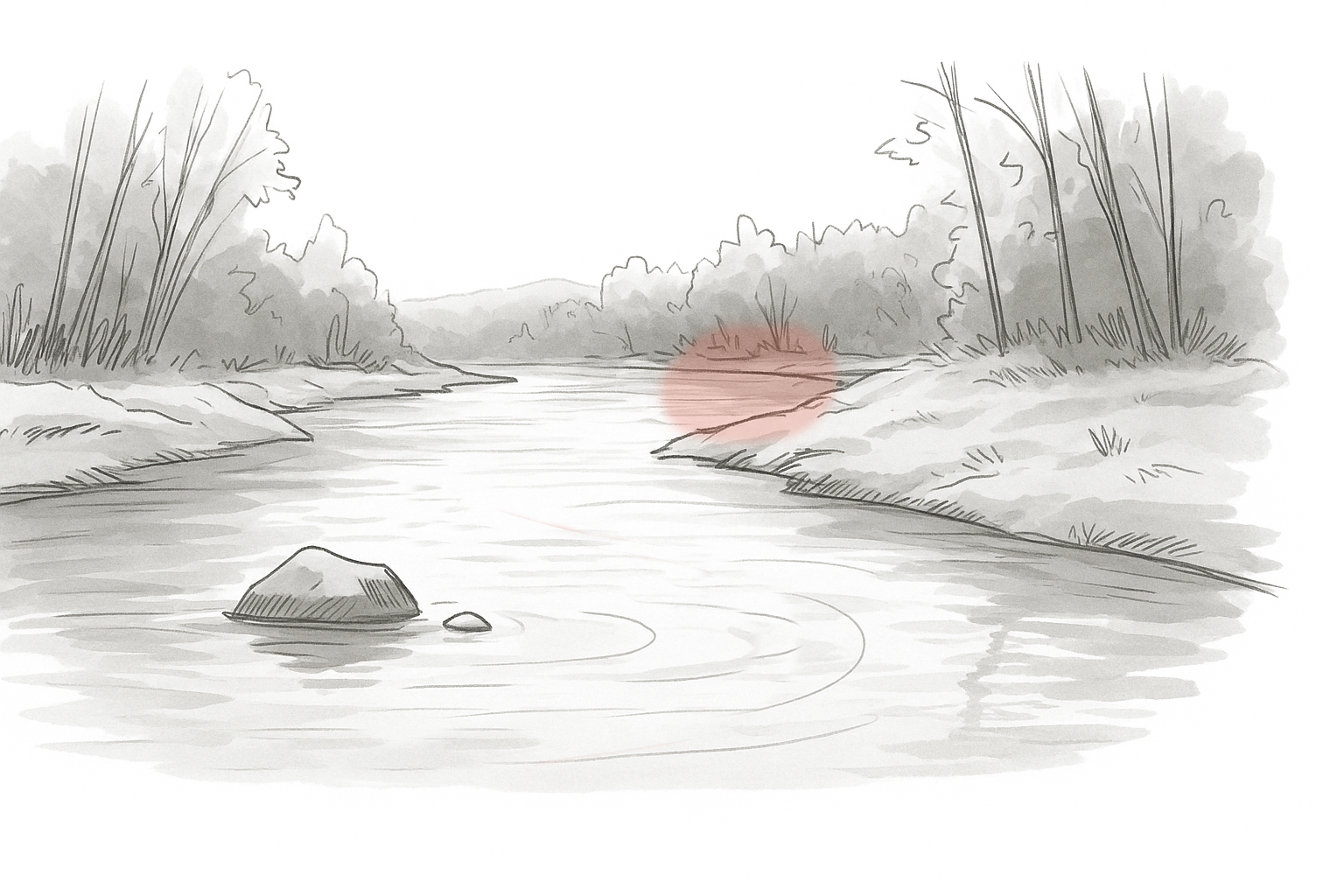

He taught me to see the river not as a uniform pool, but as a landscape of different neighborhoods where fish live for different reasons. We weren't looking for the fish themselves; we were looking for the *places* a feeding fish would be. He pointed out a spot where fast water met slow water, creating a visible line or "seam."

"Think of that seam as a conveyor belt for food," he explained. "A smart steelhead will sit just inside that slow water, watching everything that gets swept by in the fast lane. It's a low-effort way to get a high-calorie meal."

Suddenly, the whole river changed for me. I stopped looking at the obvious deep holes and started seeing the subtle clues: the tail-out of a pool where the water shallows and quickens, a current break behind a big rock, or a deep trough on the outside bend of the river. These were the dining rooms, and that's where we needed to send our invitation.

Lesson 2: The Art of the Perfect Drift

On that first trip with Ron, my old instincts kicked in. I cast my spawn bag out and watched my float bob along. After a few casts, Ron stopped me. "You're not fishing," he said gently. "You're just drowning a hook."

He explained that my spinner spinning past those fish on the Au Sable years ago was the equivalent of a waiter sprinting through a dining room. The presentation was unnatural.

Steelhead are wary, and anything that looks out of place - a bait moving too fast, too slow, or being dragged unnaturally across the current - is a red flag.

The goal, he taught me, is a "dead drift." The bait must travel at the exact same speed as the current, tumbling along the bottom as if it were a natural egg, worm, or nymph that had been dislodged upstream.

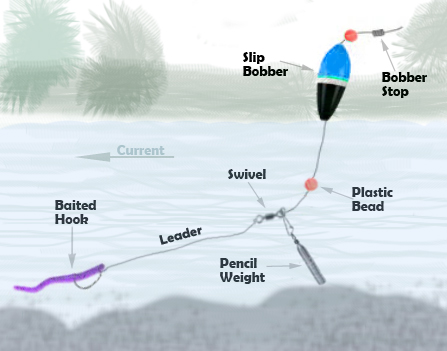

My float wasn't just a bobber; it was a speed gauge. If my float was moving faster than the water around it, my line was dragging the bait. If the float was moving slower or getting pulled under, I was snagged on the bottom.

"Your bait should lead the float, not the other way around," he instructed. "And you want to feel that little *tick... tick... tick* as your weight bounces along the bottom. That's how you know you're in the zone." It took practice, mending the line and controlling the slack, but when I finally got it right, I felt involved with the riverbed. I'd never experienced this before. I wasn't just fishing the water; I was fishing the bottom five inches of it.

Lesson 3: The Right Wand for the Magic

Part of my childhood frustration came from my gear. I was using a standard 6-foot spinning rod, which was like trying to perform surgery with a baseball bat. Ron handed me his rod, and it was a revelation. It was a 10-foot "noodle rod," long and willowy, paired with a spinning reel spooled with light line and an even lighter fluorocarbon leader.

The long, flexible rod acted as a giant shock absorber, protecting the light leader from the violent headshakes of a powerful fish. It also gave me incredible line control, allowing me to hold my line up off the water to achieve that perfect, drag-free drift.

Ron explained the setup was a system. The float indicates the drift. The long rod controls the line and absorbs the shock. The light fluorocarbon leader is nearly invisible to a line-shy steelhead. The reel's smooth drag is the safety valve that lets a fish run without breaking off. Every piece had a purpose, all working together to present a tiny offering in the most natural way possible and then survive the chromatic chaos that followed.

Lesson 4: The Buffet Line

As a kid, I had three or four spinners. If they didn't want it, I was out of luck. Ron opened his vest and showed me a collection of small boxes. It looked like a tackle shop.

There were spawn bags in a rainbow of mesh colors - bright orange and chartreuse for stained water, subtle white and pale peach for clear conditions. There were plastic beads that perfectly imitated single salmon or trout eggs. There were small marabou jigs, wax worms, and even a few spinners for specific situations.

"You never know what they'll want on any given day," he said, tying on a small, dime-sized bag of fresh spawn. "You have to be willing to change things up. If spawn isn't working, try a bead. If the bead isn't working, try a jig. You're not trying to force-feed them; you're trying to offer them the one thing on the buffet line they can't resist."

The Payoff: Surviving the Chrome Rush

After an hour of practicing the drift, it finally happened. My float shot sideways and disappeared with a violence that was nothing like a snag. I lifted the long rod, and it bowed over, pulsing with a life force that sent a jolt straight through my arms.

"Fish on!" Ron yelled, a huge grin on his face.

The next thirty seconds were pure pandemonium. A silver torpedo erupted from the river, cartwheeling through the cold November air before crashing back into the water and peeling line from my screaming drag. My heart hammered against my ribs.

"Let him run!" Ron coached from a few feet away. "If he jumps, dip your rod tip down. Don't horse him!" He seemed much calmer than I was.

I did my best to follow his instructions, but my adrenaline was red lining. Steelhead fishing was finally fun!

The fish made several powerful runs, but the long rod cushioned every surge. Slowly, and with great excitement, I worked it closer to the bank. Ron slipped the net under a amazing fish, a twenty-six inch male with a perfect crimson stripe down its side and a jaw full of attitude.

As I crouched down in the water, looking at that beautiful steelhead, all the years of frustration washed away. I understood why people get hooked on steelhead fishing.

That trip wasn't just about catching a fish. It was about solving a puzzle. It was about understanding the river, and finally learning the game. My dad caught his share of steelhead, but I probably was too hard-headed to learn. I'm fortunate that someone gave me a second chance at it!

Ron was right. The steelhead has the final say, but by learning his lessons, I finally knew how to make a convincing argument.