I have a friend that used to be in the wildlife control business in Bay City, Michigan. He somehow landed a contract to remove beavers from an entire county's ditch and culvert system.

He wasn't allowed to sell the pelts due to county government red tape in the contract, but there was nothing stopping other people from doing so.

He would get a list of beaver dams and sightings from the county road commission. It was his job to destroy the dams. He did a lot of the dam destruction with dynamite. Some dams he was able to use hand tools to destroy, but before he did either, I got a heads-up.

I was able to cut my teeth on these county beavers. I learned a lot about their habits, their terrain, their family units, and the destruction that they can do. Most importantly though, I learned how to trap beaver.

I can't give you a list of active beaver dams like my friend would give me, but I can give you decades of trapping know-how, learned through experience, trial and error, and sometimes just plain dumb luck.

Understanding the Ditch Engineer

Before we talk about traps and sets, we need to understand the adversary. A beaver living in a pristine northern pond and a beaver plugging a county culvert are the same animal, driven by the exact same instinct: the primal need for deep, stable water.

Deep water is their fortress. It protects them from coyotes and bobcats, it keeps their den entrances hidden, and it allows them to float food and building materials with ease.

The difference isn't the beaver; it's the environment. The "ditch beaver" has adapted to a world of straight lines, man-made channels, and artificial choke points.

They don't have the luxury of a vast wilderness to work to their liking. Instead, they use our infrastructure to their advantage.

A 36-inch culvert is, to a beaver, a fantastic head start on a dam. A narrow drainage ditch is an easy-to-plug channel that can quickly flood a neighboring cornfield, creating the deep-water haven they crave.

These colonies are often comprised of a family unit: a mated adult pair, kits from the current year, and juveniles from the previous year. When you see one plugged culvert, you're not dealing with one beaver; you're dealing with a crew of 4 to 8, sometimes more, all working to maintain their watery homestead.

They are masters of their small domain, and to trap them, you have to learn to read their specific, man-altered blueprint.

Reading the Ditch and Culvert Map

Forget about picturesque lodges in the middle of tranquil ponds. Trapping county beavers is about reading the subtle signs along ditch banks and roadways.

- The Plugged Culvert: This is Ground Zero. It's the most obvious and often most active spot. Look for a buildup of mud, sticks, and corn stalks packed against the upstream side of a road culvert.

If the water level is significantly higher on one side of the road, you have an active dam. This is the beaver's primary engineering feat and your primary trapping location.

- Ditch Dams and "Check" Dams: As you walk the ditches leading away from the main culvert, look for smaller, secondary dams.

These "check dams" are built to raise the water level in the ditch itself, allowing the beavers to swim safely further from their main den. These are excellent, lower-traffic locations to pick off secondary beavers in the colony.

- Bank Dens: In ditch systems, classic stick lodges are rare. The vast majority of these beavers live in bank dens. Look for an entrance hole, which will be underwater, but you can often spot the tell-tale "slide" or muddy trail on the bank above it where they enter and exit.

You might also see a "vent hole" further up the bank, which can look like a small, unimpressive hole but leads to the main chamber. The key is finding the underwater run leading to the den entrance.

- Feed Trails and Canals: Look for narrow channels dug from the main ditch into a farmer's field or a nearby woodlot. These are food routes.

A beaver will chew down corn stalks or saplings and float them back down these canals to their main pond or feed bed---an underwater pile of branches that serves as their winter pantry.

- Castor Mounds: These are the territorial signposts. Along the straight banks of a ditch, look for small, pie-shaped mud patties at the water's edge. They will often have a dark, oily stain from the beaver's castor glands. Finding a fresh one tells you a dominant beaver is actively working that stretch of ditch.

The Tools for a Mucky Job

This is not "finesse" trapping. It requires heavy-duty, reliable gear that can function in mud, muck, and cold water.

- Traps: The workhorse is the 330 Conibear-style bodygrip trap. Its 10x10-inch opening is perfectly suited for culverts and ditch runs. For setting on bank slides and at castor mounds, a large foothold like an MB-750 or a CDR on a drowner system is the tool of choice.

In many nuisance situations, **snares** are also incredibly effective and efficient, especially in tight runs or on slides. Always check your local regulations regarding their use

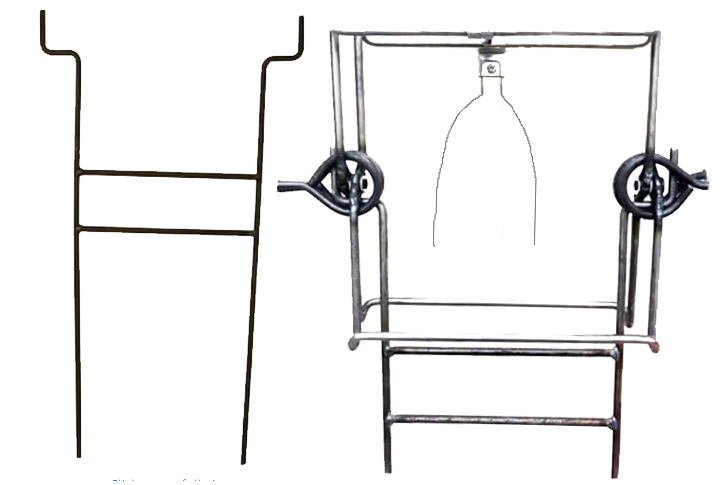

- Support & Anchoring: You cannot just plop a 330 in the mud. You need a support system. H-stands made of rebar are essential for holding your trap stable and upright in a run.

For anchoring, don't underestimate the suction of deep mud. While rebar stakes work, cable stakes driven deep are often better. For drowner setups, a long piece of rebar driven at an angle into the bank or a heavy sack of concrete (a "drowner weight") will do the job.

- Safety First, Last, and Always: You need three critical safety items. One, a good pair of trap setters to compress the powerful springs. Two, a safety gripper to hold the springs compressed while you position the trap. Three, insulated, waterproof gauntlet gloves and a sturdy pair of chest waders.

Three Sets for the County Beaver

My friend's dynamite was effective, but trapping is an art. These three sets, perfected in the drainage ditches of Bay County, will put fur in your shed.

1. The Culvert Set: The Choke Point

This is your bread and butter. The beaver is using the culvert as a pre-made dam component, and you're going to use it as a perfect funnel.

- How-To: Place your 330 on a stand just inside the upstream opening of the culvert. The goal is to have the trap almost entirely submerged. If the water is too high, set it right at the mouth.

Use sticks, driven into the mud above and to the sides of the trap, as "blocking." This blocking forces the beaver, who is coming to inspect its dam or pass through, to go *through* the trap jaws rather than over or around them.

Anchor your trap well; a 60-pound beaver caught in the current can create tremendous force.

2. The Ditch Run Set: The Ambush

This set targets beavers as they travel their ditch highways between feeding areas and their den.

- How-To: Find a narrow spot in the ditch, ideally where the banks are steep. Place your 330 on a stand in the middle of this run. The trap should be fully submerged.

To ensure the beaver doesn't swim over the top, place a large "dive stick" or "pole" across the ditch, right on the water's surface and directly above your trap.

The beaver's natural instinct is to dive under the obstacle, sending it straight into the trap. This is a subtle, deadly set that often connects with wary, educated beavers that might be shy of a culvert.

3. The Castor Mound/Slide Set: The Territorial Challenge

This is where your foothold traps shine. It targets the dominant beaver's territorial instinct.

- How-To: Find a prominent castor mound or a well-used slide coming out of the water. Build a small underwater shelf with mud, about 4-5 inches deep, right where the beaver would place its foot to climb out.

Bed your foothold trap solidly on this shelf. The trap must be attached to a drowner wire or cable that is staked in deep water. Remake the castor mound with fresh mud and apply a smear of quality castor lure.

Castor lure is commercially available from literally thousands of manufacturers.

When the big male comes to re-mark his territory, he'll place his foot on your pan and the drowner system will do the rest.

Hard-Won Wisdom

Trapping these ditch systems taught me a few things the books don't always cover. First, water levels can change fast. A heavy rain can flood your sets, and a dry spell can leave them high and dry. Be prepared to adjust.

Second, the bottom of these ditches is often soft, unforgiving muck. Use longer stakes than you think you need and make sure your H-stands are pushed in deep and solid.

Finally, be aware of your surroundings. Ditch bottoms are notorious for hiding sharp metal debris and broken glass.

You're often working near roads, so be mindful of traffic and be discreet with your sets.

My friend with the dynamite contract showed me where the beavers were, but the beavers themselves taught me how to catch them. It's a game of out-engineering the engineer.

It requires grit, smarts, and a willingness to get wet and muddy. But when you pull up a trap and feel the solid weight of a prime, blanket beaver, you'll know there's no better feeling in the trapping world.