Probably forty-five years ago, I read an article about two Michigan high school kids that came across an idea to trap more effectively. I think it was entitled "Remember the 45," but I'm not really sure. I've forgotten a lot of small details from the late 70s and early 1980s, but what I do know - for sure - is that I "Remember the 45."

I believe it was Michigan-based outdoor writer Tom Huggler that wrote an article about it. He was referencing a trap placement that he and his high-school trapping friend had perfected.

The set was a dirt hole set, a small hole punched into the ground or dug into a nearby bank, with a smelly concoction inside to lure the neighboring coyotes, fox, and raccoons.

These two high school pals found that one trap in front of the dirt hole was far less effective than two traps set at 45-degree angles to that dirt hole.

Their logical thought, and probably a pretty good one, was that a wary fox wouldn't come straight in like a dog going to its food bowl. It would sneak in from a side, trying to avoid potential trouble. It didn't matter which side it snuck in on; he was had!

The article was about the friend, signing Tom's yearbook with something like "Good luck in the future." And he added - "Remember the 45!"

I don't know either one of those guys personally, but I have remembered the 45 and it has paid off for me throughout the years. I would have loved to have learned more about their other trapping techniques, but that wasn't the gist of the article.

It would take me years to find out what worked best for me, and now, this article will spell it out for you.

The Why Behind the Dirt

Before we even start pounding in stakes, we need to get inside the animal's head. Huggler and his friend were onto something because they weren't just thinking about bait; they were thinking about behavior.

A dirt hole is so effective because it's a triple threat that masterfully exploits a predator's core instincts.

First, there's greed. The bait you place deep in that hole smells like a free, easy meal that another animal has stashed for later.

In the tough world of a Michigan winter, no fox, coyote, or raccoon is going to pass up the *promise* of calories.

Second is curiosity. A patch of freshly dug earth and a dark, mysterious hole is a powerful visual magnet in an otherwise undisturbed landscape.

It's like a billboard that screams, "Hey! Something interesting happened here!" They simply have to check it out.

Finally, and most importantly for canines, is territoriality. When you add a dash of lure and a squirt of urine, you're not just offering food; you're leaving the calling card of an intruder.

A dominant coyote or fox is biologically wired to investigate and challenge any newcomer to its turf. The dirt hole becomes a place they feel compelled to visit.

Location: 80% of the Battle

You can build the most beautifully constructed dirt hole set in the world, but if it's in a place predators don't travel, you'll burn gas checking empty traps.

The best set in a bad location is worthless. Here in Michigan, our landscape gives us two primary theaters of operation, each with its own set of rules.

Southern Michigan Farmland: Think of this as a land of highways and intersections. Predators use edges to travel.

- Fencerows and Field Edges: These are the I-75s of the predator world. Walk these edges and look for tracks in the mud, droppings (scat), and natural funnels.

- Inside Corners: Where two fencerows meet, or a woodlot juts into a field, it creates an inside corner. Animals flowing along these edges are naturally funneled right into that corner. It's a deadly spot for a set.

- Isolated Features: In the middle of a cut bean field, a single clump of tall grass or a lone rock is a magnet. Predators use these as scent posts and navigation aids. These features make for perfect "backing" - the object your dirt hole is dug next to, which forces the animal to approach from the front, right over your trap.

Northern Michigan Big Woods: Up north, the cover is vast, and you have to think differently.

- Two-Tracks and Logging Roads: These are the main arteries. Animals, just like us, prefer the path of least resistance. The intersection of two logging roads is a fantastic place to start looking.

- Habitat Transitions: Pay close attention to where one type of habitat meets another. The edge of a cedar swamp bleeding into a hardwood ridge, or a ten-year-old clear-cut growing up into thick popples - these "seams" are where prey animals are abundant, and predators spend their time hunting.

- High Points and Knolls: A coyote especially loves to get on a high, sandy knob to survey its domain and catch the wind. You don't want to put your set right on the very peak where it will be silhouetted. Instead, place it just off the crest, where the trail leads up to the vantage point.

Nuts and Bolts: Building the Classic Single-Trap Set

Before you can master the "45," you need to be able to build a rock-solid, single-trap dirt hole with your eyes closed.

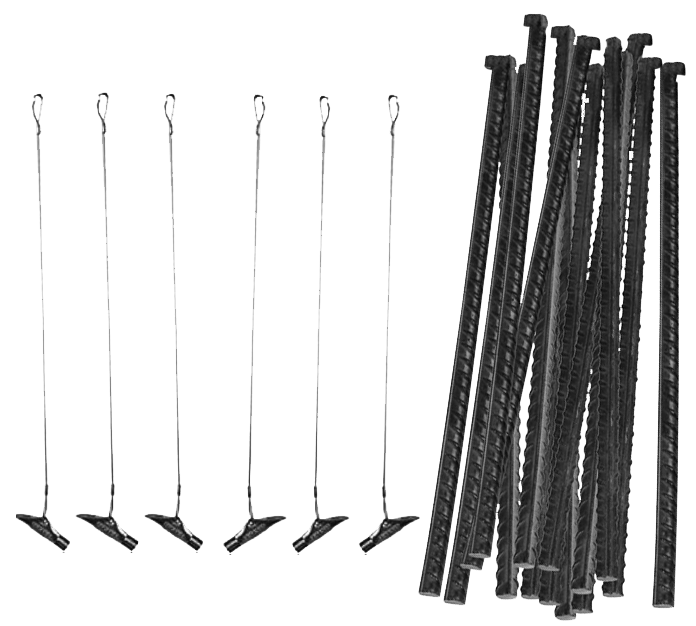

This is your foundation. Grab your gear - a trusty #1.75 or #2 coilspring trap, a digging tool, a hammer, sifter, and your bait and lures - and let's build one.

1. Pick Your Backing: Find that grass clump, stump, or rock we talked about. The backing dictates the entire set. It tells the animal, "You can't approach from behind, so you have to come around front."

2. Dig the Bed: Don't just scalp the grass. Dig a trap bed deep enough so that when your trap is set and bedded, the pan is about an inch below the surrounding ground level.

Make the bed a little bigger than the trap itself. Clear out any rocks or roots.

3. Drive the Stake: Pound your rebar or cable stake in deep and right in the center of the bed. A Michigan coyote in January, hooked up on frozen ground, will test every bit of your anchoring system. Make it solid.

4. Bed the Trap: This is the step that separates the pros from the amateurs. Place your set trap over the stake. Now, using your fingers, pack dirt *under the jaws and levers* and inside the jaws until that trap is absolutely immovable.

It should feel like it grew there. If it wobbles, tilts, or crunches in the slightest, a wary fox will dig it up, or a coyote will simply back away. It must be rock solid.

5. The Hole: Now, dig your actual dirt hole. Place it about two inches behind the trap pan. Punch it into the ground at a 45-degree angle, aiming down and under the backing.

Make it about 8 to 10 inches deep and just a couple of inches wide. That angle and placement naturally guide an animal's foot onto your trap pan as it leans in to sniff the hole.

6. Sift and Blend: Place a pan cover (a piece of poly-fill, screen, or even a big leaf) over the trap pan to keep dirt from getting underneath it.

Now, using your sifter, cover the entire trap with about a half-inch of fine, dry dirt. Use a whisk broom or a branch to gently blend the edges of your set pattern into the surroundings. The only thing that should look out of place is that inviting dark hole.

7. The Finishing Touch: Drop a thumbnail-sized piece of bait deep into the hole. Put a smear of long-distance call lure on the top lip of the hole or the backing. Finally, add a squirt of fox or coyote urine on the backing to sell the story that another animal was just here.

Graduating to "The 45"

Now for the set those high-school kids perfected. The "45" is a thing of beauty for trapping wary, educated canines that might be shy of a head-on approach. The location principles are the same, but you'll need a slightly wider, flatter spot.

The process starts the same: pick your backing and dig your bait hole first. Now, visualize two lines extending out from the sides of that hole at 45-degree angles. This is where your traps go.

You'll dig two separate trap beds, one on each of these 45-degree lines. The front jaw of each trap should be about 6-7 inches from the edge of your bait hole. Bed and stake each trap just as solidly as you did with the single set.

The key is pan placement. You want the pans of the two traps to be roughly 9-10 inches apart from each other, creating a wide "kill area" in front of the hole.

When an animal comes in, it might not commit to the center. It may circle, sniff, and try to work the set from the left or the right. With the "45," it doesn't matter.

As it creeps in from the side to get a better angle on the bait hole, its foot falls naturally onto the pan of the left or right trap. You've just doubled your chances and outsmarted the smartest coyote on your line.

Another benefit: If you've ever made your late morning trap check and found that a fox had dug up your trap, the 45 would have nailed him as he was digging it.

Sure, it's twice the work, but sometimes the 45 is just what the doctor ordered for a specific animal.

Fine-Tuning for Your Target

- For Fox: They are light-footed and cautious. Ensure your trap pan tension isn't too heavy, and blend your set meticulously. The classic single set or the "45" are both deadly, but be extra vigilant about solid bedding. A fox will feel the slightest wobble.

- For Coyotes: Bolder and more aggressive. The "45" is a phenomenal coyote set because they love to circle. You can use a slightly larger backing and a bit more visual appeal (a bigger dirt pattern). Don't be afraid of a strong-smelling gland lure here.

- For Raccoons: The bulldozers. Solid bedding is non-negotiable, as they will dig and pull at anything. A single, head-on dirt hole is often plenty for a coon. Use a sweet, fish-based bait and put it deep in the hole to force them to really work for it, ensuring a good foot placement on the pan.

The dirt hole, whether a classic single or a slick "45," is the foundation of a successful fur line in Michigan. It's a craft that demands practice and attention to detail.

Don't get discouraged by a snapped trap or a near miss. Every set, catch or not, is a lesson. Pay attention to what the animals are telling you, and soon you'll be the one with the hard-won knowledge to share.

Most trappers, I believe, start out dirt hole trapping. This new spin on things can help when the fox is out-foxing you.

Good Luck!